The Rev. Dr. Robert Warren Spike was a leader in the American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, serving as the first Executive Director of the Commission on Religion and Race of the National Council of Churches. In that position he rallied the resources of America's mainline Protestant and Orthodox Churches in support of the August 28, 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, then organizing a massive lobbying effort to support the passing of both the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. In previous years the National Council had taken “cautious” positions on calling for racial justice, often doing “little more than encourage further study.” 1 The assassination of Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963 energized the Council's new Commission to picket and pray, and advocate for major national legislation.

In that position he was joined by African-American politician, educator, and civil rights leader, Dr. Anna Arnold Hedgeman, who served as the Commission's Coordinator for Special Events. For the March of Washington they bussed in tens of thousands of white church people from all over America. They also launched “Operation Sandwich” to make sure food was available for all the March participants. It could have been called the feeding of the hundreds of thousands.

The Commission worked with Robert Moses and the Rev. Arthur C. Thomas to initiate and support the Freedom Summer of 1964 by recruiting young people to work for the controversial Mississippi Delta Ministry. Their activism included organizing “Freedom Schools” in the most racially segregated counties in the country. Their efforts to register black voters was deeply threatening to the white power structure of Mississippi. The NCC launched a training program for the student volunteers in Oxford, Ohio, but on June 21, 1964 three of the earliest volunteers - Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Swerner - were arrested and then viciously murdered. It fell to Dr. Spike to inform the other volunteers on what had taken place.

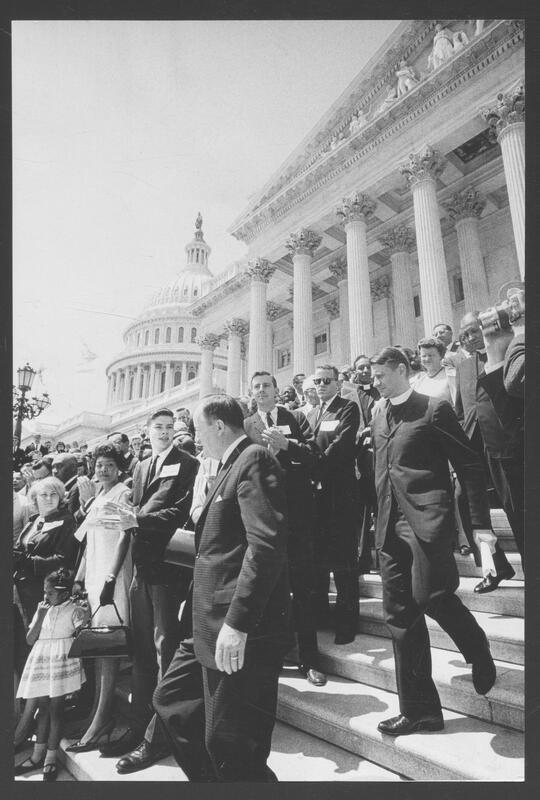

Dr. Robert W. Spike (left), Executive Director of NCC’s Commission on Religion and Race, and Sen. Hubert Humphrey (center) on the Capitol steps during a demonstration urging passage of the civil rights bill, 1964. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-104, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Robert W. Spike (left), Executive Director of NCC’s Commission on Religion and Race, and Sen. Hubert Humphrey (center) on the Capitol steps during a demonstration urging passage of the civil rights bill, 1964. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-104, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Anna Arnold Hedgeman, Dr. Robert W. Spike, and Bishop B. Julian Smith reviewing NCC programs. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-100, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Anna Arnold Hedgeman, Dr. Robert W. Spike, and Bishop B. Julian Smith reviewing NCC programs. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-100, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Marian Anderson, Paul Newman, Roy Wilkins, Dr. Robert W. Spike, and Faye Emerson arriving in Washington for civil rights rallies, 1963. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-99, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Marian Anderson, Paul Newman, Roy Wilkins, Dr. Robert W. Spike, and Faye Emerson arriving in Washington for civil rights rallies, 1963. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-99, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Robert W. Spike and other NCC leaders meet with President Lyndon B. Johnson, 1963. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-101, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Robert W. Spike and other NCC leaders meet with President Lyndon B. Johnson, 1963. Religious News Service Photographs, RNS RG 1, RT 1040-101, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

In 1966, after the passage of the two ground breaking laws, Dr. Spike took a position at the University of Chicago Divinity School, but continued to be active in civil rights work in Mississippi and Washington.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said of Dr. Spike, “He was one of those rare individuals who sought at every point to make religion relevant to the social issues of our time. He lifted religion from the stagnant arena of pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities. His brilliant and dedicated work...will be an inspiration... We will always remember his unswerving devotion to the legitimate aspirations of oppressed people for freedom and human dignity... As we continue to grapple with the ancient evils of man's inhumanity to man, we will be sustained and consoled by Bob's dedicated spirit.” 2

Dr. Spike (November 13, 1923- October 17, 1966) was born in Buffalo, New York, and educated at Denison University in Ohio and Colgate Rochester Divinity School in Rochester, New York. He later received his doctorate from Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary. Originally an American Baptist, he briefly served as an associate at the First Baptist Church (now United Church) in his college town of Granville, Ohio, before becoming pastor of Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square in Greenwich Village, New York City from 1949 to 1956. While there Dr. Spike also took standing in the Congregational Christian Churches, and the Judson Church soon dual aligned there as well. In 1956 he began to work for the national Congregational denomination (soon to be part of the United Church of Christ) at their New York headquarters, and with the reorganization of the work in the United States became the General Secretary (second ranking position) of the United Church Board for Homeland Ministries until 1963.

In 1945 Dr. Spike married Alice Coffman, and they had two sons, Paul and John.

At this point readers, you may be impressed with Dr. Spike's attainments, but might be wondering why this biography is on the LGBTQ-RAN website? Let me explain.

Spike's son Paul has written a book on his father, which the New York Times writer Christopher Lehmann-Haupt said calls us to “participate in its comedy, its terror, its extreme pain, and ultimate triumph.” 3

In 1965 Paul entered Columbia University, which is close to the Interchurch Center on Riverside Drive, where the National Council of Churches had its offices. A few months later at a nearby bar, he met a minister, whom he identifies as “Ted Walsch,” who worked for his father at the Commission. They talked about the Vietnam War and President Johnson's words. Near closing time Walsch asked Paul if he would “feel like coming over to my place for a nightcap?” There Ted discussed Paul's father, and then shifted to talking about sex. Paul realized “Ted must be a homosexual,” and “He's making a play for me.” Ted was mixing this conversation with talk about Paul's father. Paul finally asked if “Ted” thinks his father is a homosexual? “Yes. He is, if you mean does he have sex with men.” Walsch contends that he had not had sex with Dr. Spike, but “he'd probably like to.” Ted later says, “Your father is obviously bisexual.” Paul states “I don't think I'm a queer,” and leaves, rejecting the come on. 4

The next morning Paul called up his mother and told her what happened. Later that day his father called him from Chicago, angry, upset, asserting that much of Walsch's statement was rubbish, but not all of it. He is going to fly to New York City immediately to speak to his son in person. When they do speak, his father tells him, “There was... (sic) an element of truth in what he told you.” 5 Over the next weeks and months, they have further conversations and Paul realizes that it is important that he accept his father’s sexuality, and not take it as a betrayal.

Early that fall Paul goes to dinner with a friend and his father. Dr. Spike is concerned that the government is trying to undercut the Child Development work being in done in Mississippi. Government funding is to be withdrawn. Dr. Spike believes that this decision is being taken to appease the Chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, John Stennis of Mississippi, in order to gain funding for Vietnam. R. Sargent Shriver, John Kennedy's brother-in-law, and then the head of the Office for Economic Opportunity and advisor to President Johnson, is the “hatchet-man” in this operation. Dr. Spike refers to Shriver as “one of the nastiest men I have ever met.” He then reports, “He threatened me.” “He said, 'The FBI knows about you, Reverend Spike.'” 6 One can only imagine what J. Edgar Hoover had been compiling on Dr. Spike. Spike knew his phone was tapped.

On October 16, 1966, Dr. Spike spoke at the dedication of a new Christian Center at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. The building included a guest room for visiting dignitaries. The next morning his body was discovered “in a pool of blood. The back of his head had been bludgeoned and was gaping open. He was dead.”

“No clues were found. No murder weapon. There were signs of a violent struggle. But no traces of the murderer, not even a fingerprint.” 7

Within a day “There are certain things the Columbus police are saying to the newspapers.” They cited some magazines they called pornographic. 8 Soon it was being described as a sexual pick up gone bad. However, the lack of any fingerprints might suggest it was a professional hit. The same day that the murder was in the national press there was another article that read that Sargent Shriver had criticized “clergymen who want to interfere in the domestic programs of the federal government. I am shocked to find some clergymen resorting to character assassination tactics to protest an administration decision.” 9

Consolations flooded in from Dr. King, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Stokely Carmichael, Vice President Humphrey, Whitney Young, Victor Reuther, and many more. SCLC leader Hosea Williams later said, “We don't believe these assassinations are an accident. We believe there is a conspiracy.” He related this death to those of John and Robert Kennedy, and Dr. King. 10

The Columbus police issued more inflammatory comments. They interviewed many of Dr. Spike's close associates, beginning, “Did you know that Rev. Spike was a homosexual?” A lawyer working for the National Council of Churches tells the family that the Columbus police have told them he was “under observation in New York and Washington. They have evidence that he had homosexual experiences.” 11

Sometime later the Columbus police arrest a suspect who had been breaking into local churches and robbing them. Soon he was charged with the murder. Then suddenly they dropped the charges when the suspect was found to have been a patient in a mental hospital at the time of the murder. 12 No one else was ever arrested or charged.

In his second edition, Paul Spike speaks of reading Taylor Branch's prize-winning biography of Dr. King. He writes, “Secret fears and hatreds had abruptly stifled grief. Jack Pratt, the general counsel hired by Spike in 1963...” for the Council's Race Commission, “...warned that public resolution was 'the last thing" his colleagues should seek... [the death ] with homosexual literature nearby... these alien clues suggested an unspeakable plot to smear the victim, until Pratt made clear that any trial would unearth a forbidden world along with a few witting clergy who had shared, restrained or protected Spike's furtive liaisons with men.” Branch reported that the results of Pratt's report: “...unnerved church officials [to ] shut down the inquiry for damage control...” James F. Findlay wrote that “a certain quietness descended in church circles to blot out further discussion of his work in the sixties.” 13

At the time of Dr. Spike's death I was a young seminarian at a United Church of Christ and American Baptist school. He was a hero to us before his death, we were shocked at the murder. But soon thereafter found our school acting as if he had never existed

When the marriage equality movement began, Ambassador and minister Andrew Young, Dr. King's right-hand man, spoke to the United Church of Christ General Synod offering strong support. He said, “Most people do not know that many of the people who helped in central parts of the Civil Rights movement were lesbian or gay. Some worked in national settings at that time for they could survive more in the big city than in local churches. After the work that they have done I feel I should return the favor, and encourage support for their Civil Rights as well.” 14

Robert Spike died three years before the Stonewall riots. His tragic death at the age of 42 denied him the opportunity to explain his own life to us. He cared for his wife, and he loved his sons. We do not know if he would have considered himself to be bisexual, gay, or troubled or confused in that secretive and oppressive time. Yet his unfailing and energetic work on behalf of others should be honored and respected by all.

Dr. Spike's publications include In but not of the World (1957); Safe in Bondage (1960); To Be a Man (1961); Civil Rights Must Model for Mission (1965); and The Freedom Revolution and the Churches (1965). His papers are housed at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago Library. A smaller collection focusing on the Freedom Summer of 1964 is at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

(This biographical statement was written by Richard H. Taylor and was edited by Paul Spike.)

1 See Margaret Bendroth, Good and Mad: Mainline Protestant Churchwomen, 1920-1980, (Oxford University Press, 2023) p.144. Dr. Bendroth also cites historian James Findlay.

2 Quoted in Paul Spike, Photographs of My Father: A Lost Narrative from the Civil Rights Era, (Cinco Puntos Press, 2016, 2 nd Edition) pp.179-180.

3 Ibid., back cover review.

4 Ibid., pp.143-148.

5 Ibid., p.151.

6 Ibid., pp.165-167.

7 Ibid., p.155.

8 Ibid., p.174.

9 Ibid., p.176

10 Ibid., pp.179-182, and back cover review.

11 Ibid., pp.184-185.

12 Ibid., p.195.

13 Ibid., pp.216-217. The Findlay quote is quoted from his book, Church People in the Struggle.

14 Quote from Ambassador Young, verified by him through the good aid of his daughter Lisa Alston, January 21, 2024.

Biography Date: July 2024

“Rev. Dr. Robert Warren Spike | Profile”, LGBTQ Religious Archives Network, accessed February 15, 2026, https://lgbtqreligiousarchives.org/profiles/robert-warren-spike.