Becki Jayne Harrelson, a queer artist who refuses to shy away from the imagery and implications of Orthodox Christianity, has made a notable impact on queer theology since 1993. Harrelson’s bold creativity, spanning over decades of work, has become its own provocative art genre, inspiring countless others to not only embrace queerness, but also center queerness in traditional Christian spaces.-

Born on August 17, 1954, Harrelson grew up in a family full of Baptist and Pentecostal ministers who outspokenly condemned queerness. Experiencing childhood sexual and psychological abuse and homophobia, Harrelson struggled to exist in a religious conservative setting, especially upon recognizing that she was queer herself. When she finally came out to her mother in 1985, Harrelson was told she was possessed by demons and destined for Hell. Even in these difficult circumstances, Harrelson remained curious about spirituality and biblical scholarship, finding a great affinity to the original words and teachings of Christ. Harrelson experienced two near-death experiences before the age of six, and, while she has limited memories of what happened, she remembers an incredibly loving presence surrounding her.

Harrelson’s family was also heavily involved with Gospel music. Her maternal grandmother was a church organist, and her great aunt Eva Rose was a Chicago pianist who played at famous jazz clubs and famously received a one-hundred dollar tip from Frank Sinatra himself. Harrelson fondly remembers her great aunt’s “no BS” attitude and immediate acceptance of her coming out as a lesbian, saying that, “Nothing is wrong with her; she was born this way.”

Harrelson, with all the musical influences in her family, grew up learning the French horn and hearing music in her head throughout childhood and adulthood. However, because of her oppressive family and traumatic childhood, she stayed away from music as creative expression for most of her life.

Her life changed when she experienced a spiritual reawakening in 1991. As Harrelson was healing from her childhood traumas, she began seeing gay images of Christ that were the antithesis of all she was taught. These images shocked Harrelson herself, to the point that she tried to suppress them for years. However, after years of her family defining God and Jesus for her, Harrelson decided to claim Christ as her own, especially seeing Christ as a figure for everybody. In her own words, Harrelson describes her spiritual breakthrough as “[seeing ] the Christ, the Buddha, God within all of us as we are, and we are born in grace, not original sin.” Despite no longer identifying as Christian, she has been drawn to spiritual teachers and leaders like the Buddha, Bart Ehrman, Raymond Charles Barker, Ernest Holmes, and Kennedy Schultz.

Harrelson was also heavily influenced by the passing of the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policies under president Bill Clinton. Recognizing that the conservative Christians she has known and grown up with all her life were to blame for not allowing openly queer people into the military only fueled Harrelson’s fire and compelled her to start creating and sharing her queer-forward art with the world as a voice of activism and defiance.

Harrelson herself can be considered a jack (or jane) of many trades, finding success in many fields like art, writing, marketing, advertising, graphic design, and website design and development. Before becoming a full-time artist, Harrelson had studied at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville in 1973 and spent five years working up to a senior account position at Atlanta-based advertising agency Gordon Bailey and Associates Inc. She also worked at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution for eight years as an internet and editorial manager.

Despite never receiving a formal art education, Harrelson showed great talent for visual art, especially in her style of mimicking Renaissance-era Christian iconography. Harrelson studied the work of Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio, as well as modern artists. References to their work and visual puns, especially those alluding to modern queer life, are hidden on her canvases. Making art has been a form of meditation and prayer for Harrelson: she begins each painting with a sanctifying ritual that includes prayer, music, incense, and anointing the canvas with oil. All her models have been queer people in real life.

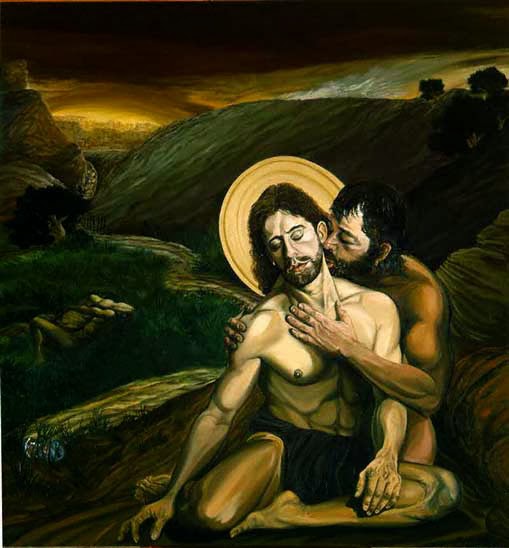

Judas Kiss

Judas Kiss

The catalyst for her art career is the life-sized oil painting titled Judas Kiss, in which Jesus Christ and Judas Iscariot are seen in a homoerotic embrace. Harrelson followed up this image with a series depicting classic Bible stories from a lesbian feminist point of view, including the Madonna with a female partner (who is based on Harrelson’s own lesbian partner since 1995), Jesus rescuing a drag queen from a stoning, and a feminine Holy Spirit resurrecting Christ.

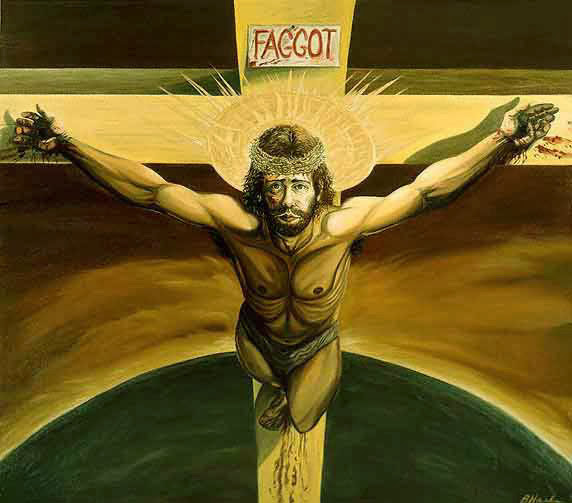

These works finally led to Harrelson’s most discussed and controversial piece The Crucifixion of Christ. Hanging above Christ’s lifeless body on the cross is a sign that, instead of reading “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” simply reads “faggot.” Despite what might seem to be a straightforward message-that Christ himself was gay–Harrelson approached this piece with the purpose of de-shaming human sexuality, especially queer sexuality, and presenting it as a sacred act. Harrelson has also noted that the word “faggot” could be replaced with any term of human discrimination, saying, “Anytime anyone rises up in condemnation, hatred, or violence against another, Christ is crucified.”

Crucifixion of Christ

Crucifixion of Christ

Over the course of her art career, Harrelson has received condemnations from both conservative Christians and queer people alike. Her work has been censored in her own hometown of Atlanta, given its Bible Belt locale, and even queer gallery owners have avoided showing her pieces in fear of public retaliation. Queer folks have also criticized Harrelson for using Christian imagery that may be interpreted as inherently homophobic. Harrelson’s choice to paint men, despite herself being a lesbian, and using queer slurs like “faggot” have caused further controversy within queer spaces.

Even amid the criticism, Harrelson’s art has also received a wide array of critical acclaim. Her work has been exhibited in Taos, New Mexico, as well as the Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation in New York City. Numerous print and online publications have featured her, including LGNY, New York Blade, Girlfriends Magazine, Tikkun, and JesusInLove.org. Harrelson is also included in the book Art That Dares: Gay Jesus, Woman Christ & More by Kittredge Cherry.

Still calling Atlanta home, Harrelson lives with her partner and is a freelance marketing consultant. A self-proclaimed “lipstick lesbian,” Harrelson also enjoys writing political commentary. In 2010, she injured her back, as well as her dominant shoulder and arm, becoming unable to draw and paint. In response, Harrelson began producing music in 2012 and, as of September 2023, has copyrighted forty of her original compositions under Sunnybeck Music, a nod to her frequent childhood association with Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. Regardless of her chosen modality, it is clear that Harrelson offers prolific insight that not only uplifts the inherent love taught by Christ, but also empowers the queer community to continue subverting harmful religious rhetoric in the name of social and political activism, creative freedom, and liberation.

(This biographical statement written by Allie Knofczynski for a Queer and Trans Theologies class at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities with information from Harrelson's website and an interview with her. Harrelson has reviewed this statement.)

Biography Date: December 2023