Rev. Cecil Williams, renowned pastor of Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco and advocate for LGBTQ justice, was born in San Angelo in West Texas in 1929. Cecil was the fourth of five boys—and a sister—born to Sylvia Lizzie Best and Earl Cuney Williams. Earl supported the family by working as a janitor in a white church. Cecil’s mother helped set a path for him at an early age by nicknaming him “Rev.”

The town at that time was rigidly segregated, the railroad tracks being the dividing line. Cecil and his siblings went to a Black school, shopped in Black-owned stores and found community in the Black Wesley Methodist Church. Experiences of racism, discrimination and powerlessness were regular occurrences during Cecil’s childhood. Around the age of 12, Cecil began a bout of horrifying visions and frightening voices. Diagnosed as a “nervous breakdown” which persisted for several months, Cecil withdrew from social settings and found refuge at home as he tried to fend off these terrors. With the support of his family, Cecil gradually re-emerged with a stronger sense of self and power.

Cecil thrived in school and was recognized as a leader, serving as class president throughout elementary and high school. The Williams family was musical and regularly sang together in harmony. Cecil was a particularly gifted singer and was often called upon to perform. Cecil sought opportunities to test the boundaries of segregation which he did cautiously, yet bravely. Yet in the larger society he regularly heard messages of “You are nothing….you are worthless.” One particularly terrifying experience occurred when his high school track coach arranged for Cecil and other athletes to compete in a track meet in Tuskegee, Alabama. The coach drove them in his car, providing these young men some glimpses of a world larger than West Texas. However, when they stopped for food on the trip home, they were attacked by a group of white men, causing damage to the car and injuring the coach.

Cecil was destined for a career in the church from an early age. As a youth, he often presided over “church” with siblings and friends. Even at that time, Cecil was adamant about his imaginary church welcoming persons of difference races and backgrounds. He received an Exhorter’s License at age 19. During college he and his brothers traveled throughout the South to sing as a gospel quartet. He saw his career path as college, seminary and then pastoring a large church in a big city.

While studying sociology at Sam Huston College in Austin, Texas, Cecil was deeply influenced by J. Leonard Farmer, Sr., the first Black Texan to earn a Ph.D. (from Boston University) and also a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church South. Farmer guided Cecil into new, broader biblical and theological thinking. Farmer also strengthened Cecil’s self-confidence and served as a model of higher levels of achievement.

As Cecil was finishing college in 1952, he was invited by a group of Methodist seminarians to apply to Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University. The students were working with the Perkins administration to become the first major educational institution in the South to integrate voluntarily. Cecil was one of five Black seminarians to enroll at Perkins that fall. The dean promised to shield the students from egregious acts of racism, but Cecil and his colleagues knew they were being closely watched and expected to maintain proper protocol in dealing with white students. Cecil interned at the large, Black St. Paul Methodist Church where the Rev. I.B. Loud served as a haven and a sounding board for the Black seminarians. Cecil appreciated the academic regimen at Perkins. And he chafed at the strictures, like being discouraged from participating in civil rights protests that were happening at the time. Tensions mounted at the beginning of their third year when some seminary board members decried that the dorms had been integrated—Black students were living with white students. The other Black seminarians agreed to move off-campus but Cecil held fast and threatened to withdraw from school. Rev. Loud intervened and encouraged Cecil to do whatever it took to complete the degree and get his credentials. Then he would be in a stronger position to work for change in the church and society.

Cecil admits that his dream after seminary was to become the first Black pastor of a large white congregation. Yet his desire for such acceptance was anathema to white church leaders and also threatening to Black clergy who were comfortable with the status quo. In 1955, he was appointed by the Black bishop in West Texas to a small Black congregation in Hobbs, New Mexico. During his year in Hobbs, he married a school teacher, Evelyn Robinson. He then accepted a faculty and chaplaincy position at Huston-Tillotson College (his alma mater had merged with Tillotson). In 1959, he was about to receive an appointment to a prestigious congregation, Wesley Methodist Church in Austin, but that was blocked by other Black clergy. Williams was disappointed and discouraged and left the parish to do graduate studies at the University of Texas and Pacific School of Religion. In 1960, he moved to Kansas City and became pastor of St. James Methodist Church. Here he finally had the opportunity to work on racial integration in churches and to lead civil rights actions as the co-chair of the local Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) chapter.

In 1963, Williams was invited by Bishop Donald Tippett to visit Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco. Glide was a large facility with a significant endowment and small white congregation in the gritty Tenderloin ghetto. The bishop was drawing on the endowment to enable an urban ministry experiment there. Williams immediately saw the potential to realize his dreams of empowering diverse persons to fuller lives. He joined three other clergy doing community outreach at the Glide Urban Center. The focus of the Urban Center was to develop community services to respond to persons’ needs.

Ted McIlvenna, a Glide colleague, was instrumental in organizing the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH), a coalition of clergy and LGBTQ leaders to address injustices against LGBTQ persons. When CRH planned a Mardi Gras dance and fundraiser for January 1, 1965, Williams was one of the clergy who negotiated terms and security with the police department. Williams and the other clergy were horrified by the large-scale police harassment at that event and held a press conference the next day to express their outrage. (More information in CRH exhibit: https://exhibits.lgbtran.org/exhibits/show/crh)

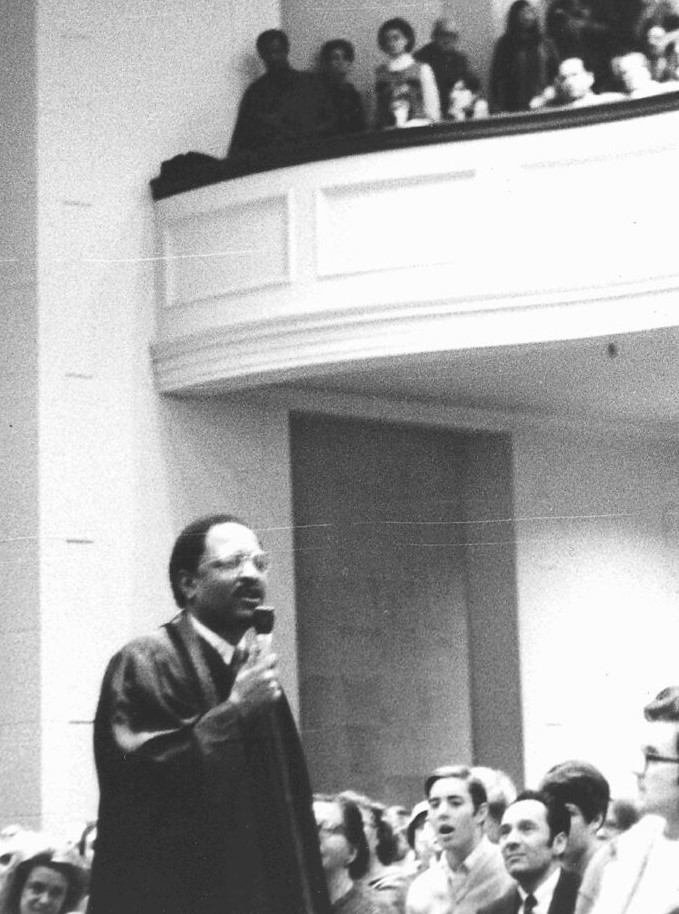

Williams realized that developing social service programs was not his forte, so he became the pastor of the congregation in 1965. Williams saw an opportunity to open the doors of the church to all persons, proclaiming a radically inclusive Gospel message of unconditional love to each and every person. However, the remaining 35--mostly elderly and white--members were comfortable in their refuge and resistant to change. Williams and the remnant congregants clashed as he challenged them to a new vision and model of being the church. The office received racist threats and messages. Members walked out of his sermons. Eventually all but two of the original members left, but Williams gradually built a new, diverse and thriving congregation.

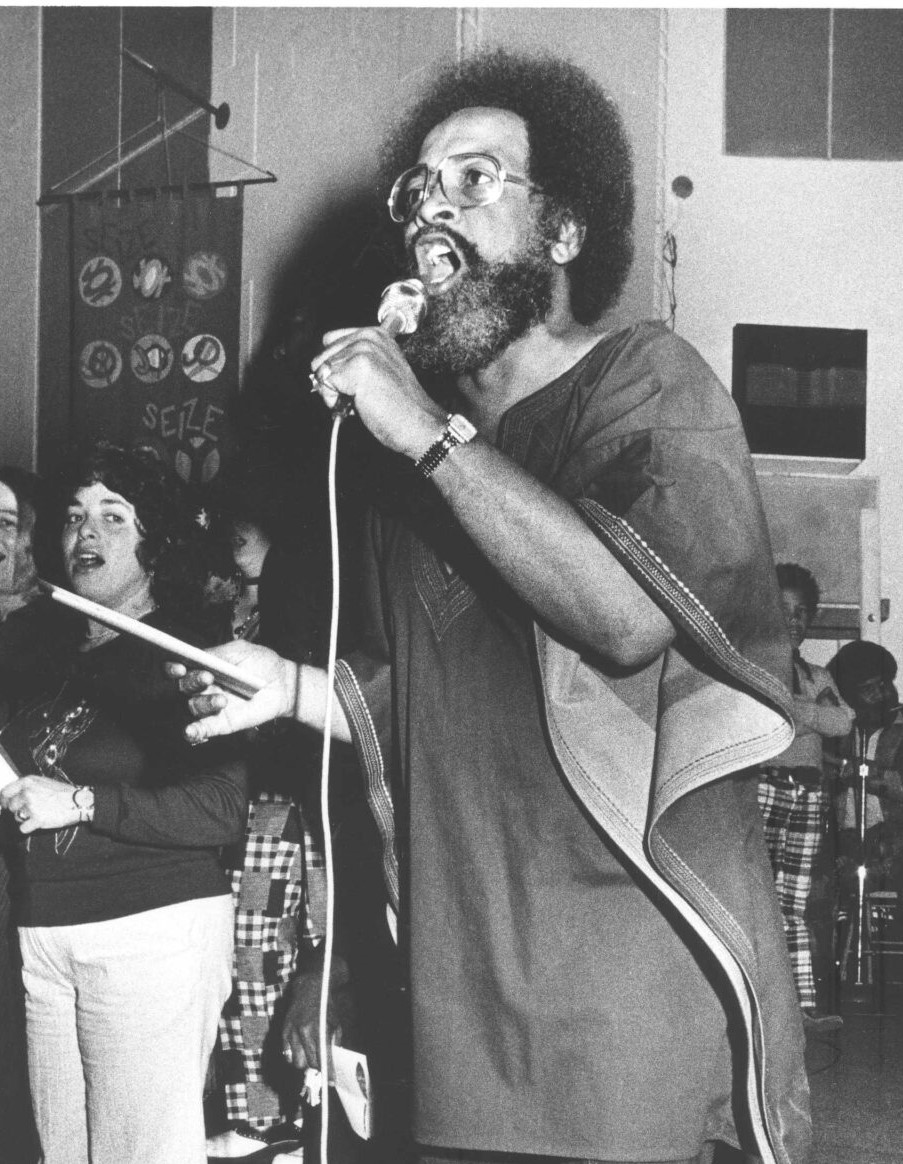

To carry out this transformation Williams dramatically changed the Glide Sunday service. A Gospel musical ensemble replaced the choir singing traditional hymns. He stripped the sanctuary of traditional church trappings which he saw as vestiges of hierarchy. Most controversial was the decision to remove the large cross hanging on the back wall and replace it with banners and photos of diversity, peace, justice and equity. At the same time Glide radically changed Williams and his appearance. He gave up wearing a clerical collar for African dashiki and red pants. He grew his hair long, into an Afro. The Sunday morning “Celebration” became powerful phantasmagoria of spirituality, music, dance, art, and community. Over several years the congregation grew to hundreds, then thousands of persons, ranging from struggling Tenderloin denizens to political leaders and media celebrities from the metropolitan area. Williams became a major religious figure as well as firebrand advocate for justice in San Francisco.

Williams focused the church’s ministry on empowering persons to self-determination. Two of these early groups were Citizens Alert, which mobilized actions to fight police harassment, and Vanguard, a collective of young queer activists. Williams and his fiery oratory were a regular presence at community actions against injustice. Over the years Williams led demonstrations and protests against the Vietnam War, nuclear energy, racial injustice, housing and job discrimination and gun violence.

Janice Mirikitani was a poet who began volunteering at Glide early in Williams’ tenure. She was instrumental in introducing poetry, dance, visual arts, fiction and film to Glide and the Sunday celebration. She became full-time staff in the late 1960s, a strong partner to Williams in developing Glide’s message and ministry. They were married in 1982. Janice also was poet laureate of San Francisco from 2000-2002.

Over the years Williams and Glide were at the forefront of advocacy for LGBTQ justice, including: fighting housing and employment discrimination; addressing trans rights; providing services for persons with AIDS; and calling for marriage equality. Williams performed same-sex unions long before they were legal. Williams spoke at many conferences and press conferences advocating full equality for LGBTQ persons in the church and in society. LGBTQ persons became a notable percentage of the Glide congregation.

Glide also developed a panoply of social services for the poor and needy, including: free meals program; child care center; legal clinic; drug testing; services for trauma recovery; and a walk-in center for those in need of housing, hygienic help or emotional support. The Glide Foundation initiated a collaborative venture to build 52 units of low-income housing near church. Williams became a prolific fundraiser for Glide and its programs. His charisma drew celebrities like Sammy Davis, Jr. Marvin Gaye, Maya Angelou, and Bill Cosby, political leaders such as Diane Feinstein and Nancy Pelosi and investor Warren Buffett into the Glide circle.

In response to the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s Williams honed in on addiction recovery as being key to Black community health and empowerment. Glide hosted conferences on responding to the crack epidemic. He embraced principles and steps to recovery and wove them into the Glide’s identity and ministry. He wrote and published No Hiding Place: Empowerment and Recovery for Our Troubled Communities (HarperCollins: 1992).

Williams retired as the pastor of Glide in 2000, but remained as spiritual leader and officer of the Glide Foundation. Janice died unexpectedly in July, 2021. Williams’ health slowly declined leading him to withdraw from public work in 2023. He died at his home on April 22, 2024.

(This biographical statement written by Mark Bowman from information provided in Beyond the Possible by Cecil Williams and Janice Mirikitani (Harper Collins: 2013) and the sources below.)

Biography Date: May 2024

“Rev. Cecil Williams | Profile”, LGBTQ Religious Archives Network, accessed March 10, 2026, https://lgbtqreligiousarchives.org/profiles/cecil-williams.